By: Sophonias A. Kassa

Introduction

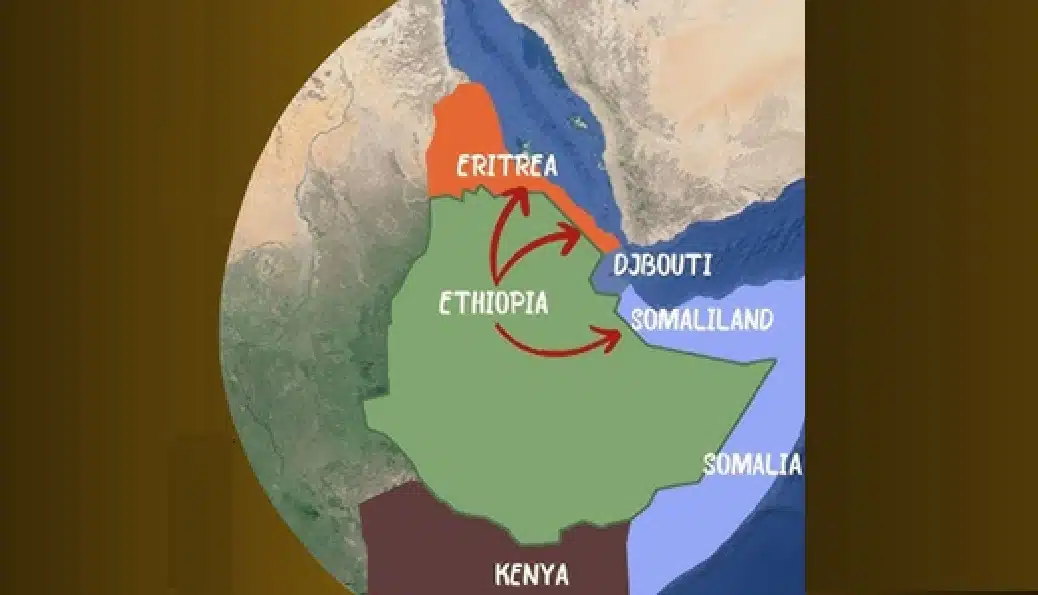

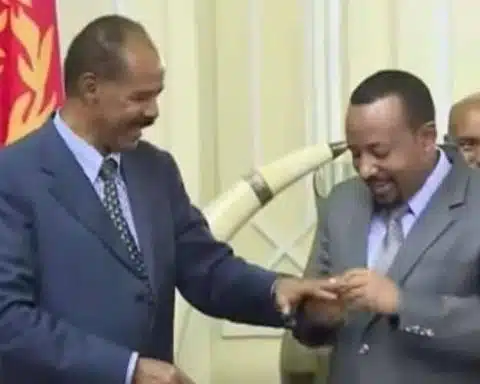

In recent months, the relationship between Ethiopia and Eritrea has deteriorated dramatically, with tensions escalating to alarming levels. After a period of relative stability between 2018 and the onset of the Tigray War, the two nations are now on the brink of renewed conflict. The dissatisfaction expressed by Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki following the Pretoria Agreement, which ended hostilities in Tigray, has introduced a significant strain in their relations. A pivotal issue lies in Ethiopia’s quest for access to the sea—a matter Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed describes as “existential” for Ethiopia (Tekuya, 2024, p. 303). The quest for maritime access carries not just economic implications but also complex geopolitical challenges that threaten regional stability.

As I reflect on Ethiopia’s aspirations for port access, it’s essential to examine this situation from multiple angles. While the need for sea access is longstanding and justified, the strategies employed to secure it provoke important questions. The pursuit of a port cannot be viewed in isolation; it intertwines with historical grievances, current geopolitical realities, and the broader consequences for the Horn of Africa. Ethiopia must consider whether its current approaches are likely to yield lasting solutions or exacerbate instability in the region.

Legal and Diplomatic Aspects of Port Access

One critical aspect of this issue is the legal and diplomatic framework that governs port access. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS, 1982) grants landlocked nations the right to negotiate sea access, but it also stipulates that they cannot assert territorial claims over another state’s land (UNCLOS, 1982, p. 322). Therefore, Ethiopia’s request for ports like Assab cannot simply be a matter of demand; it requires a nuanced diplomatic engagement. The pivotal question then becomes whether Ethiopia possesses the diplomatic strength needed to negotiate favorable terms for access.

Ethiopia’s approach could involve crafting bilateral agreements with Eritrea that prioritize economic cooperation—such as investing in Assab’s port facilities and supporting Eritrea’s development needs—in exchange for port access.

Alternatively, establishing a long-term lease or a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) could provide Ethiopia with the needed access without infringing on Eritrean sovereignty. Furthermore, involving third-party mediators, like the African Union or economic partners such as the UAE and China, could potentially facilitate dialogues. These external actors have vested interests in maintaining regional stability, which might encourage them to play a mediating role between Ethiopia and Eritrea.

However, Eritrea’s historical inclination toward isolationism and its reluctance to depend on Ethiopia complicate matters (Plaut, 2017, p. 98). Ethiopia may be overly optimistic about its potential to persuade Eritrea into an agreement. While Ethiopia’s economic and military strengths are evident, establishing a foundation of trust is critical for any meaningful diplomacy, and that trust remains tenuous.

Ethiopia’s Dependence on Foreign Ports

Ethiopia’s reliance on foreign ports underscores a significant economic vulnerability. Currently, more than $1 billion is spent annually in port fees, with approximately 95% of its trade flowing through Djibouti (Al Jazeera, 2023). Although efforts have been made to diversify port usage, each alternative presents its own challenges. –

Somaliland (Berbera Port): Ethiopia has signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to lease a naval base near Berbera but faced backlash from Somalia regarding the deal (Khan & Idle, 2024, p. 911). This highlights the difficulties of securing alternatives without introducing regional tensions.

– Kenya (Lamu Port): Negotiations for access under the LAPSSET corridor project are underway, but infrastructure limitations pose significant hurdles (LAMU Report, 2024, p. 12). This raises concerns about the viability of Lamu amid ongoing logistical and security challenges.

Sudan (Port Sudan): An agreement was reached in 2018, but ongoing political instability in Sudan has stalled progress (Modern Diplomacy, 2024, p. 8). Thus, reliance on this route appears precarious. While these alternatives offer potential solutions, they do not replicate the strategic advantage that Assab provides due to its geographic proximity to Addis Ababa. This brings us to the essential dilemma: how much is Ethiopia willing to compromise for Assab, and conversely, how much is Eritrea willing to concede?

Challenges to Securing Access to Assab

Ethiopia’s pursuit of port access is hindered by complex political and geopolitical challenges. Eritrea’s unwavering control over Assab presents a significant barrier, ensuring any Ethiopian claim faces strong resistance (Tekuya, 2024, p. 311). The deep-seated distrust between the two nations, rooted in the 1998-2000 Ethio-Eritrean War, further complicates negotiations and underscores the necessity of rebuilding diplomatic ties (Negash & Tronvoll, 2000, p. 223).

Beyond bilateral tensions, external influences exacerbate Ethiopia’s difficulties. The UAE’s military presence in Assab and the strategic interests of global powers like China and the U.S. introduce additional layers of complexity, as their objectives may not align with Ethiopia’s aspirations for port access (Khan & Idle, 2024, p. 912). Meanwhile, Ethiopia’s internal instability—marked by conflicts in Tigray, Amhara, and Oromia—weakens its diplomatic leverage, limiting its ability to negotiate effectively. A government entangled in domestic strife is unlikely to assert its claims with the necessary strength and coherence. These combined factors create formidable obstacles to Ethiopia’s quest for a sustainable maritime outlet.

Why Military Action Must Be Avoided

Faced with these challenges, Ethiopia must carefully consider whether armed conflict over Assab would bring the desired outcomes. History teaches us that wars over territory often yield costly and counterproductive results, and Ethiopia must draw lessons from its own past. Initiating military action to reclaim Assab would contravene international law, violating the principles of sovereignty and non-aggression established in the UN Charter (UN Charter, 1945, Article 2(4)). Such a move would likely result in global condemnation, potential sanctions, and diplomatic isolation for Ethiopia. The financial implications of war would outweigh those of current port fees, leading to an enormous burden on an already strained economy (Al Jazeera, 2023). Furthermore, the ramifications of conflict could spread throughout the Horn of Africa, threatening to pull in neighboring countries and destabilize the region’s fragile trade and security dynamics (Tekalign, 2019, p. 189).

Rather than pursuing a path of war, Ethiopia would be wise to focus on diplomatic channels, engage in regional cooperation, and diversify its trade partnerships. The agreements being forged with Somaliland, Kenya, and Sudan demonstrate that Ethiopia has alternatives beyond military confrontation (Weldesilassie, 2022, p. 145). Prioritizing these peaceful approaches will yield far more sustainable and beneficial outcomes in the long run.

In conclusion, while Ethiopia’s aspiration for access to the sea constitutes a vital economic and geopolitical necessity, the journey toward achieving it must be navigated with caution. The range of challenges—including historical grievances, regional and global political dynamics, and internal instability—demands a commitment to diplomacy over conflict. Resorting to military action would not only breach international norms but also entail significant economic and humanitarian costs, endangering the delicate stability of the Horn of Africa. Ethiopia ought to focus on solidifying existing agreements, enhancing regional economic ties, and engaging in thoughtful diplomatic negotiations. With patience and strategic finesse, Ethiopia has the potential to secure sustainable access to ports and foster peace in the region. Ultimately, the long-term well-being of Ethiopia and neighboring nations relies on solutions grounded in diplomacy rather than impulsive military actions.

References

- Al Jazeera. (2023, November 7). Is landlocked Ethiopia starting another war over ports in Horn of Africa?Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com

- Ghebremeskel, G. (2019). Ethiopia and Eritrea: Economic integration and the future of port access.Journal of African Studies, 45(3), 115-130.

- Khan, S., & Idle, A. F. (2024). Exploring the implications of the Somaliland-Ethiopia MoU: Trade, security, and diplomacy.International Research Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 5(1), 901-916.

- LAMU Report. (2024). Ethiopia’s strategic engagement with Kenya’s Lamu port.African Development Journal, 12(1), 11-16.

- Modern Diplomacy. (2024). Ethiopia-Somaliland deal: A geopolitical shift in the Horn of Africa.Retrieved from https://moderndiplomacy.eu

- Negash, T., & Tronvoll, K. (2000). Brothers at War: Making Sense of the Eritrean-Ethiopian War.Ohio University Press.

- Plaut, M. (2017). Understanding Eritrea: Inside Africa’s Most Repressive State.Hurst & Company.

- Tekalign, Y. (2019). Regional security dilemma for Ethiopia’s quest for access to the sea.African Security Review, 28(3-4), 189-206.

- Tekuya, M. E. (2024). Swimming against the current: Ethiopia’s quest for access to the Red Sea under international law.Fordham International Law Journal, 47(3), 301-326.

- (1982). United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.United Nations.

- Understanding War. (2024). The implications of Ethiopia’s recognition of Somaliland.Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved from https://understandingwar.org

- Weldesilassie, A. (2022). Ethiopia’s port diversification strategy: The shift from Djibouti to multi-port access.African Economic Policy Journal, 39(2), 145-162.